Mobilenews24x7 Bureau (Book Excerpt)

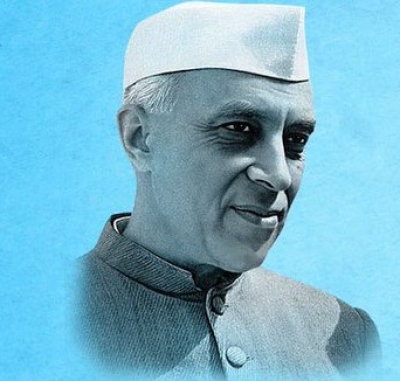

Contemporary Indian history is incomplete without the mention of Jawaharlal Nehru. The impact of various decisions that he made as Independent Indias first Prime Minister has been long-lasting.

Nehru was born on November 14, 1889 to a wealthy Kashmiri Brahmin family settled in Allahabad. His father, Motilal Nehru, had a flourishing law practice at the Allahabad High Court. Although always surrounded by people at home, Nehru’s childhood was �sheltered and uneventful’.

His private tutor, Ferdinand T. Brooks, helped him develop an aptitude for reading and initiated him into the world of science: “We rigged up a little laboratory and there I used to spend long and interesting hours working [on] our experiments in elementary physics and chemistry.”

In his teens, Nehru was impressed by Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05. He thought of India’s freedom and “Asiatic freedom from the thraldom of Europe”, and nationalist ideas filled his mind.

In May 1905, he set sail for England for further studies. After two years at Harrow, Nehru joined Trinity College, Cambridge. It was there that he read Meredith Townsend’s �Asia and Europe’, which influenced his political thoughts.

Meanwhile, back home, Nehru’s father had got active in politics. Though he was happy with the development, Nehru did not “agree with his politics”, possibly because his father was too much of a moderate. He completed his higher education from the University of Cambridge in 1910, studied law, was called to the Bar, and finally returned to India after a seven-year stay in England to begin a law practice.

STEPPING INTO POLITICS

Nehru’s first political foray was a speech at a public meeting, sometime in 1915, to protest against an anti-free press law.

“As soon as the meeting was over, Dr Tej Bahadur Sapru, to my great embarrassment, embraced and kissed me in public. This was not because of what I had said or how I had said it. His effusive joy was caused by the mere fact that I had spoken in public on the dais.”

Nehru’s political career took off when he began to participate in the mass movements initiated by Mahatma Gandhi.

Over the years, Nehru emerged as the foremost leader of the Congress party and the global voice and face of the country’s freedom struggle. He was “wholly absorbed and wrapt” in Gandhi’s non-violent forms of protestations. He was first arrested towards the end of 1921, after mass protests had broken out in the wake of the Prince of Wales’ visit to India.

He was incarcerated on several occasions in the years that followed; he was jailed for almost three years for his participation in the Quit India Movement. During this time, Nehru wrote two of his most popular books — �The Discovery of India’ and �Glimpses of World History’.

As the country arrived on the cusp of Independence, Nehru was positioned by Gandhi as free India’s first PM. On August 15, 1947, close to midnight, he delivered the famous speech, �Tryst with Destiny’.

MOULDING THE NEW NATION

As a PM, Nehru adopted a liberal and democratic approach towards his ministerial colleagues. Five of the 14 ministers in his first Cabinet were non-Congressmen. And while disagreements broke out between him and some of his Cabinet colleagues, Nehru refrained from sacking the dissenting members. Ministers, like Syama Prasad Mookerjee and B.R. Ambedkar, who felt strongly, left of their own will.

He was instrumental in overseeing the creation of various centres of excellence. The All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) was established in Delhi — its foundation stone was laid in 1952. The Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs) came up during his tenure. The first Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) was set up in 1951 in Kharagpur. The IITs and IIMs are today globally recognised for their excellence and have grown in number.

The Atomic Energy Commission of India was also established in August 1948, with a view to harness atomic energy for the nation’s need to maintain peace.

Nehru was particularly influenced by the Communist experiment in Russia and believed in the virtues of economic development within a socialistic framework. Senior Congress leader C. Rajagopalachari parted ways with Nehru in 1957 over the PM’s economic prescription for the country.

Rajaji opposed government control over the private sector. Non-partisan commentators, too, were critical.

“To a foreign observer valuing both men, and loving India, much of what Rajagopalachari was saying was more than telling. It was the truth.”

The Five-Year Plans executed by the Planning Commission were part of the Socialist agenda. The Nehruvian economic model proved to be a failure, as the country’s development started stagnating. Yet, subsequent regimes continued with it, until the reforms of 1991 came along and dismantled the old system for good.

TOUCHSTONE OF INDIA’S FOREIGN POLICY

Nehru’s inclination towards the policy of �non-alignment’ in dealing with the global community was evident back in January 1947, when he wrote that New Delhi must be friendly to both the US and the Soviets, but join neither camp.

As PM and External Affairs Minister, he stuck to this formula, which became the touchstone of the country’s foreign policy. Governments since then have, in spirit, treaded this path. It was at Nehru’s initiation, along with that of Josip Broz Tito and Gamal Abdel Nasser, that the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) was established in Belgrade in 1961.

In 1961, Nehru added another feather to his cap — the liberation of Goa and Daman and Diu from Portuguese rule and their integration into the Union of India. Initially, however, the PM had been reluctant to order military action to liberate the said territories. The idea had been discussed back in 1950 and Patel had observed that “it was two hours’ work”. Nehru resisted, and the matter rested there.

In 1961, his government decided to act after it failed in its diplomatic efforts to persuade Portugal to give up the occupied territories. The 17th Infantry Division, the 50th Parachute Brigade, the 1st Battalion of the Maratha Light Infantry and the 5th Battalion of the Madras Regiment were pressed into action. The Indian Navy also joined the effort, code-named as Operation Vijay. It deployed two warships off the coast of Goa.

Nehru faced some challenges on the foreign policy front, which have had a lasting impact on the nation. This was partly because his outlook was based on idealism and not ground realities. He sought the United Nations’ intervention following the infiltration and mayhem caused by armed Pakistani tribesmen, who entered Kashmir with the Pakistani state’s support in 1947.

Indian troops moved in and repulsed the offensive, pushing back the attackers. Just when the Pakistanis were on the run, Nehru approached the United Nations, which imposed a ceasefire. The part of Kashmir that was under Pakistan’s hold has since remained with it.

“This (going to the UN) was done on the advice of the governor general, Lord Mountbatten.”

The manner in which the matter played out, thereafter, shocked Nehru: “By now, Nehru bitterly regretted going to the United Nations.”

THE DILEMMA OVER CHINA

He faced another challenge in terms of foreign policy when China attacked India in 1962. Nehru had been forewarned of Chinese designs as far back as 1950 by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, who wrote to Nehru that India should strengthen its position in Tibet and Sikkim to counter the “growing Communist menace in China”.

And months before his death, Patel again wrote to the PM: “The Chinese Government has tried to delude us by professions of peaceful intentions�”.

But Nehru apparently did not take the cautions seriously, holding to the �Hindi-Chini bhai bhai (Indians and Chinese are brothers)’ slogan in letter and spirit.

Two years before the war, in 1960, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai had visited India and discussed border issues with Nehru, but the talks had led to nowhere. There was also a lingering bitterness on the Chinese side over the Nehru government’s decision to give asylum to the Dalai Lama, who had fled Tibet in 1959.

According to US-China scholar John Garver, at a meeting in 1959, Chairman Mao Zedong said that India had to be “dealt with”, as it was “doing bad things” in Tibet.

Notwithstanding Patel’s caution and Zedong’s remark, only a few people in the Indian establishment believed that China would actually launch a full-scale war. And when it did, India was caught unprepared. The Chinese completely dominated the western sector of the theatre of war, with their intelligence network having fed them accurate details of Indian positions and placements.

To make matters worse, there was demoralisation in the Indian military ranks as a result of the then Defence Minister V.K. Krishna Menon playing favourites with key officials of the Indian Army. Indian positions were overrun and the fear that China would take over Assam was real. Nehru’s remark that his heart went out to the people of Assam was seen by many as surrender. But then, the Chinese unilaterally declared a ceasefire and withdrew.

Nehru died on May 27, 1964 in the aftermath of the 1962 debacle of the Sino-Indian War, following a brief illness.

About his legacy, he had said: “If any people choose to think of me, then I would like them to say: �This was the man who, with all his mind and heart, loved India and the Indian people, And they, in turn, were indulgent to him and gave their love most abundantly and extravagantly’.”

with further agency inputs