Indian-origin researchers’ air monitor device can check for Covid, flu & RSV

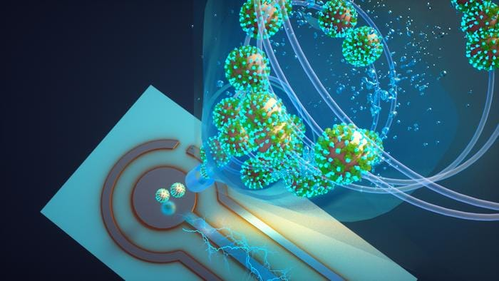

New York, July 11: A team of Indian-origin researchers has developed a real-time monitor that can detect any of the SARS-CoV-2 virus variants in a room in about five minutes.

The inexpensive, proof-of-concept device, developed by combining recent advances in aerosol sampling technology and an ultrasensitive biosensing technique, could also potentially monitor for other respiratory virus aerosols, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

It can be used in hospitals and health care facilities, schools and public places to help detect the viruses.

“There is nothing at the moment that tells us how safe a room is,” said John Cirrito, a professor of neurology at the School of Medicine at Washington University in St. Louis.

“If you are in a room with 100 people, you don’t want to find out five days later whether you could be sick or not. The idea with this device is that you can know essentially in real time, or every 5 minutes, if there is a live virus,” he added.

Published in the journal Nature Communications, the researchers called it the most sensitive detector available.

Cirrito along with Rajan Chakrabarty, Associate Professor at the varsity’s McKelvey School of Engineering and Joseph Puthussery, a post-doctoral research associate in Chakrabarty’s developed the detector by converting a biosensor that detects amyloid beta as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease.

Chakrabarty and Puthussery exchanged the antibody that recognises amyloid beta for a nanobody from llamas that recognise the spike protein from the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

The team developed the nanobody that is small, easy to reproduce and modify and inexpensive to make. They integrated the biosensor into an air sampler that operates based on the wet cyclone technology.

Air enters the sampler at very high velocities and gets mixed centrifugally with the fluid that lines the walls of the sampler to create a surface vortex, thereby trapping the virus aerosols. The wet cyclone sampler has an automated pump that collects the fluid and sends it to the biosensor for seamless detection of the virus using electrochemistry.

“The challenge with airborne aerosol detectors is that the level of virus in the indoor air is so diluted that it even pushes toward the limit of detection of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and is like finding a needle in a haystack,” Chakrabarty said.

“The high virus recovery by the wet cyclone can be attributed to its extremely high flow rate, which allows it to sample a larger volume of air over a 5-minute sample collection compared with commercially available samplers.”

Most commercial bioaerosol samplers operate at relatively low flow rates, Puthussery said, while the team’s monitor has a flow rate of about 1,000 litres per minute, making it one of the highest flow-rate devices available.

It is also compact at about 1 foot wide and 10 inches tall and lights up when a virus is detected, alerting administrators to increase airflow or circulation in the room.