New Delhi, Aug 27 : The publication of Siddharth Kak and Lily Bhan Kak’s ‘Love, Exile, Redemption: The Saga of Kashmir’s Last Pandit Prime Minister and His English Wife’, published by Rupa, has renewed the discussion on Ram Chandra Kak role as prime minister of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir in the turbulent months leading up to India’s Independence.

Was Jammu & Kashmir’s last Pandit prime minister only doing the bidding of a ‘moody maharaja’, as has been argued by Siddharth Kak and Lily Bhan Kak, or was he in cahoots, alternately, with the Political Department of the dying British Raj and Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan?

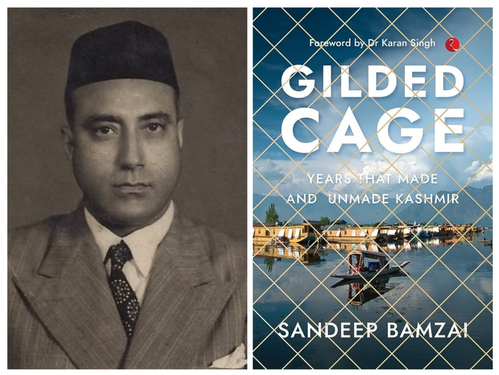

In his book, ‘Gilded Cage: Years That Made and Unmade Kashmir’, also published by Rupa, Sandeep Bamzai, Editor-in-Chief and Managing Director, IANS, argues that Ram Chandra Kak was anything but a pliant prime minister following the orders of his royal boss. Excerpts:

If Sheikh Abdullah was the protagonist of what eventually became a brutal cage match, then his bete noire was the Prime Minister of J&K Pandit Ram Chandra Kak, representing Maharaja Hari Singh in the gladiatorial contest between the monarchy and the harassed praja.

Ram Chandra Kak was a faithful servant of the autocracy. He was a hireling of the British. Actually in his case the two very much meant the same. His line of thinking was to save the former with the help of the latter. He knew world reaction was on the offensive. He knew that in the wake of the Second World War, Anglo Americans were the main spearhead of the new western axis. And they were putting heavy premium on every reactionary force in every corner of the world.

The experience of Greece, China, Turkey and Iran had taught all reactionaries that they could count on an endless supply of dollars and war material if they were sufficiently ruthless in suppressing their own people. The shrewd Kak’s policy was to save the autocracy by selling out to Imperialism. This could be done only suppressing the people’s movement ruthlessly, something that he showed great appetite for.

Kak had done his homework and he knew fully well why the British had reared 550-odd princes all these years. He knew why so much solicitude was being shown for the rights and privileges of these ‘ancient houses’. He knew their job was to form a network of friendly fortresses in a foreign territory.

He realised that Kashmir was to be one of the main bulwarks of this intricate chain. For, Kashmir was in a pre‐eminent position to play a key role in the geopolitics of the region wedged as it was on top of India and between what would be Pakistan touching the borders of China and Afghanistan.

Kak understood that in the new world order where the Anglo Americans would oppose the Soviet Union bitterly, Kashmir could become the perfect base for anti-Soviet operations. Its importance, according to Kak, was only enhanced by the Mountbatten Plan -‐ a stroke of genius -‐ as described by Leo Amery, former Secretary of State for India, which allowed two new nations to join the British Commonwealth.

The new dynamic situation opened up a plethora of possibilities for Kak. Inside the State, the national movement could be killed by the wave of communalism engendered because of the boost it got from the June 3 Plan. The British government proposed a plan, announced on June 3, 1947 that included the following principles — Principle of the Partition of British India was accepted by the British government; successor governments would be given Dominion Status; and autonomy and sovereignty to both countries.

Outside the State, one could play the two Dominions against each other, and possibly hold them at bay by deceiving both. It was a calculated plan. The good offices of Lord Ismay, Sir George Cunningham and Sir Robert Francis Mudie, ICS, were available for necessary intrigue, even as Inspector General Richard Powell, Chief of Police of the State, Major General Henry Lawrence Scott, Chief of Staff, Kashmir Army, and Col. Webb, British Resident in Srinagar, were vital to keep the liaison going, so that everything that was being done was off the map. All of them were complicit with Kak.

National Conference leaders were securely locked up. With Imperialism covering your back, who could dare challenge autocracy. This was the frame of mind in which Kak met Acharya J.B. Kripalani, president of the Indian National Congress, who was visiting Kashmir in May 1947 to convince the Maharaja to accede to India.

WHEN KAK BATTED FOR PAKISTAN

Major General Shahid Hamid, writing in ‘Disastrous Twilight ‐ Personal Record of the Partition of India’, says, “Kak, a Kashmiri Brahmin, himself took over the Prime Ministership from Sir Gopalswamy Aiyyangar ICS. He wanted to introduce reforms in the State, but Hari Singh resisted. Thereafter they fell apart and there was no love lost between them. On no occasion was his advice accepted.

“Kak, who was a constant visitor to Auk — Sir Claude Auchinleck, Commander‐in‐Chief India until Partition in 1947, when he assumed the role of Supreme Commander of British forces in India and Pakistan until late 1948 — in Delhi, was a man of strong character, completely western in outlook. He spoke fluent English; a man of the world, he was married to an English woman. Nehru thought him to be too clever and hated him. Kak was a realist and openly advocated that Kashmir should join Pakistan. He maintained that the State would get a fair deal and this would save it from the turmoil of Partition.”

There was an uncanny cogency in Kak’s chain of thought and he showed some efficiency in its execution too. But he ignored one crucial imponderable altogether.

Kak was totally blindsided by the organised strength of the people’s movement, both inside and outside the State. By simply not factoring in the people’s upsurge in his calculations or the width and depth of the crisis in the Imperialist camp, he missed a trick or two.

He also misread the hold of Hari Singh’s priest, Rajguru Swami Sant Deo, who was more powerful in helping the Maharaja conduct private negotiations with Indian leaders. There were constant comings and goings between Srinagar and Delhi by trusted emissaries.

Certain princes from East Punjab and Kripalani visited Kashmir to persuade the Maharaja to join India. This was followed by an historic visit of Mahatma Gandhi on August 1 to pressure Hari Singh and remove Kak. Hari Singh, meanwhile, also started negotiations with the Sikh mountain States on the eastern border to allow him to build a road which would bypass Gurdaspur and give him direct access to Delhi.

Shahid Hamid writes in ‘Disastrous Twilight’ that Kak continued warning Hari Singh that the people of Kashmir would rise against him if he ceded to India. The British Resident, Lt Col Wilfred Francis Webb (1945‐47), also maintained that it was logical for Kashmir to accede to Pakistan. Kak warned Hari Singh that there was danger of Muslim tribesmen descending on the Valley from the mountains, which is exactly what happened finally.

HARI SINGH BLOCKS OUT KAK

The outcome was that Hari Singh locked himself in the Palace, ignored Kak’s advice, and carried out negotiations in private. At the same time, he started cashing out his assets in Kashmir and transferring them to India and the UK. He started a dialogue with Vickers to buy an amphibious Viking for his safe passage out of the State. Vickers Viking was a single engine amphibious British aircraft used after World War One.

Soon, Kak sensed that the ground beneath his feet was slipping away. He saw Imperialism incapacitated for open intervention with men and material to keep its puppets in power. Sir CP was regarded as a statesman, generally in the know of things all the way up to Whitehall. Kak believed that the British would not leave their watch dogs to the mercy of the wolves, so he indulged in a lot of table thumping. Soon the cold truth dawned on him and this broke his heart. When he saw the Nizam pleading with the British, “We cannot believe that after more than a century of faithful alliance, the British government intends to throw Hyderabad out of the Empire against its will.”

Kak was very close to the British Resident. There is evidence which leads to the conclusion that his selection as PM was made, not only with the approval, but on the very strong recommendation of Lt-Col Webb himself.

His British wife, Margaret, might have been a factor in the new link up. There were reasons to believe that Pandit Nehru’s arrest was made by Kak at the behest of the Political Department. Panditji had made militant statements regarding the demands of the states’ peoples and asked for a complete transfer of power to the people throughout princely India.

The Political Department advised Kak to deal severely with Nehru, as any leniency shown towards him would embolden other states’ peoples’ leaders as well and this would have repercussions on the fraternity of princes.

Though the obsequious Kak and the British had a stranglehold on the administration, Hari Singh was never really in the background. Some time in the early 1930s, the first real threat to the Maharaja emerged in the form of the Muslim Conference, later to be rechristened National Conference, led by Sheikh Mohd. Abdullah.

Somehow, neither repression nor attempts at creating an inter‐communal schism could arrest the popular movement, which by 1944 had assumed gargantuan proportions and at the vanguard of which was the pamphlet, Naya Kashmir, which declared as its objective of turning Kashmir into a democratic State.

As the intensity of the political churn began to take its toll, Kak, obedient to the Political Department, and a man looking for options at all times, declared martial law in the spring of 1946. Scott called the Kashmir forces to action and even sent for two extra regiments from abroad to keep law and order.

GANDHIJI’S FOREBODINGS

During the visit of Gandhiji to Kashmir in August 1947, the following conversation reportedly took place between him and the Maharaja: “What is the strength of your armed forces?” asked Gandhiji. “Ten thousand” was the Maharaja’s answer. “How many are Kashmiris?” came Gandhiji’s counter. “Almost none” was the Maharaja’s reply.

As his secretary, Pyare Lal, records: “Gandhiji had always had uneasy forebodings about Kashmir and tried his best to prevent it from becoming a potential menace to peace between the two dominions.”

Even at such a crucial moment Maharaja Hari singh would not allow the Father of the Nation to visit his state. The Maharaja wrote to Lord Mountbatten that he considered Mahatmaji’s visit to his state to be “inadvisable from all points of view”, and he requested Mountbatten: “He (Mahatamaji) or any other political leader should not visit the state until conditions in India take a happier turn.”

Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru was distressed to hear the views of the Maharaja and on July 28, 1947, wrote to Gandhiji: “I shall go ahead with my plans. As between visiting Kashmir when my people need me there and being the Prime Minister, I prefer the former.”

In his letter to Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru dated August 6, 1947, Mahatma Gandhi gave some details of his talks with Maharaja Hari Singh, Maharani Tara Devi and Ram Chandra Kak. He said: “During my interviews with the Prime Minister, Ram Chandra Kak, I told him about his unpopularity among the people. He wrote to the Maharaja that a sign from him and he would gladly resign. The Maharaja had sent me a message that he and the Maharani were anxious to see me. I met them. Both admitted that with the lapse of British Paramountcy, the true paramountcy of the people of Kashmir would commence. However much they might wish to join the Union, they would have to make the choice in accordance with the wishes of the people. How that could be determined was not discussed at the interview.”

Events that followed Gandhiji’s visit were very significant. On August 11, Kak resigned. This was followed by the release of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah and other leaders.

HOW THE TIDE TURNED AGAINST KAK

… After the plan to partition the country and create the two Dominions of India and Pakistan was announced on June 3, 1947, Mohammad Ali Jinnah began his machinations, making every effort to cause a rift between Hari Singh and Indian leaders, thus preventing the state’s proposed accession to the Indian Union.

To facilitate this process, he sent a detailed set of instructions to the Muslim Conference in Kashmir that they should advocate sovereign independence for the State and oppose tooth and nail any suggestion made by other political parties in favour of accession to India.

The Muslim Conference leaders, who in the normal course were anxious that the State should accede to Pakistan, could not follow the significance of this directive. So, Chaudhari Hameedullah Khan, president of the Muslim Conference (MC), and a few other leaders met Jinnah in Delhi. Jinnah’s plan was simple — as soon as Kashmir claimed independence and refused to accede to the Indian Union, then it would be quite easy to force its accession to Pakistan at an appropriate time.

They were then told to give all possible assurances to the Maharaja that the MC would stand by the State’s independent status, so much so that Hameedullah Khan publicly stated that if ever Pakistan tried to invade Kashmir, he would be the first person to take up arms and fight Pakistan.

In addition, Jinnah assured Kak through the Nawab of Bhopal that not only would Pakistan respect Kashmir’s sovereignty, but also if India refused to sign a Standstill Agreement with the State and imposed economic sanctions, Pakistan would help in every possible manner.

The foreign minister of Bhopal was the intermediary. He visited Kashmir many times to convey these secret assurances. When Mahatma Gandhi was to visit, the MC general secretary asked for JInnah’s instructions on whether there should be hostile demonstrations or not, and in reply, Jinnah sent a cryptic message: “Leave that rogue to the tender mercies of Kak.” (Secret note from D.N. Kachru, private secretary to Nehru)

Fortunately, some documentary evidence of the Bhopal foreign minister’s secret missions and also letters written by Jinnah fell into the Maharaja’s hands and resulted in Kak’s sudden dismissal (pressure from Gandhiji during his visit to Srinagar was also responsible) just before August 15.

Jinnah, shrewdly understanding that his instructions were miscarried, sent Sheikh Sadiq Hassan and Nawabzada Rashid Ali Khan, Muslim League leaders from Punjabm to Kashmir with instructions that the MC should reverse its stand and launch a campaign demanding the State’s immediate accession to Pakistan.