First 3-D Printed Human Cornea Developed In Hyderabad

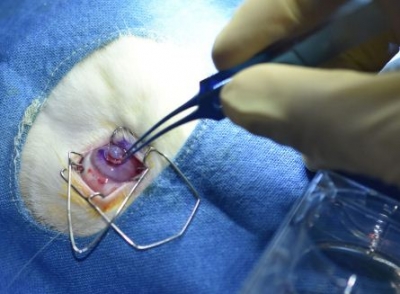

Hyderabad, Aug 14: For the first time in India, researchers in Hyderabad have successfully 3D-printed an artificial cornea and transplanted it into a rabbit eye.

Researchers from L.V. Prasad Eye Institute (LVPEI), Indian Institute of Technology Hyderabad (IITH), and the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB), have collaborated to develop a 3D-printed cornea from a human donor corneal tissue.

Developed indigenously through government and philanthropic funding, the product is completely natural, contains no synthetic components, is free of animal residues and is safe to use in patients, said a joint statement issued by the three research institutes.

Sayan Basu and Vivek Singh, lead researchers from L.V. Prasad Eye Institute, believe this can be a ground-breaking and disruptive innovation in treating diseases like corneal scarring (where the cornea becomes opaque) or Keratoconus (where the cornea gradually becomes thin with time).

“It is a made-in-India product by an Indian clinician-scientist team and the first 3-D printed human cornea that is optically and physically suitable for transplantation. The bio-ink used to make this 3D printed cornea can be sight-saving for army personnel at the site of injury to seal the corneal perforation and prevent infection during war-related injuries or in a remote area with no tertiary eye care facility,” they said.

The cornea is the clear front layer of the eye that helps focus light and aids in clear vision. Corneal damage is a leading cause of blindness worldwide with more than 1.5 million new cases of corneal blindness reported every year. Corneal transplantation is the current standard of care for cases with severe disease and vision loss.

There is a huge gap between the demand and supply of donor corneal tissue worldwide, which is further complicated by the lack of adequate eye-banking networks, especially in the developing world. Less than 5 per cent of new cases every year are treated by corneal transplantations due to donor tissue shortage.

With recent advancements in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering, the researchers from LVPEI, IITH and CCMB used decellularized corneal tissue matrix and stem cells derived from the human eye to develop a unique biomimetic hydrogel (patent pending) that was used as the background material for the 3D-printed cornea.

According to researchers, because the 3D-printed cornea is composed of materials deriving from human corneal tissue, it is biocompatible, natural, and free of animal residues. In addition, since the tissue used for this technology is derived from donor corneas that do not meet the optical standards for clinical transplantation, this method also finds unique use for the donated corneas that would otherwise be discarded.

Although corneal substitutes are being actively researched throughout the world, these are either animal-based or synthetic. Pig or other animal-based products are unsuitable for India and major parts of the developing world because of issues related to social and religious acceptability. In contrast, these human tissue-based 3-D printed corneas are not only safer but are also more affordable for patients with corneal blindness in India, they said.

Each donor cornea can aid in the preparation of three 3D-printed corneas. In addition, the cornea can be printed in various diameters from 3 mm to 13 mm and can be customized based on the specifications of the patient. This can potentially offer a solution to the shortage of donor corneas for transplantation and has great clinical significance.

However, the printed corneas will need to undergo further clinical testing and development before they can be used in patients, and this may take several years.

It will be interesting to see how the bioprinted cornea would integrate and contribute to vision restoration by modulation of the pathological microenvironment. Multiomic approaches would be used to understand these processes, says Dr Bokara Kiran Kumar, Senior Scientist, CCMB, one of the lead investigators of the project.

This research was funded by a grant from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India, and the translational work leading up to clinical trials in patients will be funded through a grant from Sree Padmavathi Venkateswara Foundation, Vijayawada.