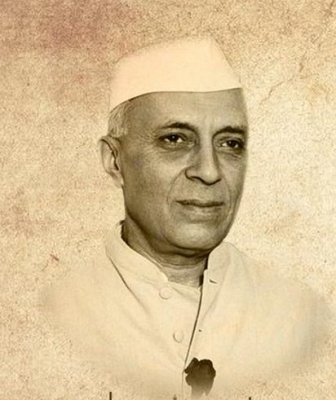

– Jawaharlal Nehru in Delhi on June 23, 1946, speaking to members of the press after being forced to come back by the Indian National Congress when he was interned at the Uri Dak Bungalow for two days by Maharaja Hari Singh’s forces as he tried to enter Kashmir.

When the decoloniser Lord Mountbatten arrived in India in March 22, 1947, to replace Viceroy Lord Wavell, the short order was to execute the transfer of power from the British Crown to India. However, that was the myopic view of looking at the issue.

The complexity was far greater though, for it involved in partitioning India, viz. Punjab on the west and Bengal in the east. It meant that he had to engage with the Congress and the Muslim League and concurrently try to bridge the trust deficit between the two parties. There was also the small matter of bringing the 560-odd egotistical princelings into the new Dominions of India and Pakistan.

As Mountbatten began his confabulations with the Indian leaders led by the key quartet — Gandhi, Nehru, Patel and Jinnah — there were many imponderables that needed answers. Nehru for instance was quick to realise that Mountbatten was on a mission. And that mission was to give independence to India. So, Nehru asked a simple question during these discussions: Do you have plenipotentiary powers? When he got an answer in the affirmative, he realised that the countdown to I-Day had begun.

By June 4 that year, in an address, Mountbatten laid down the tentpoles: “Since my arrival in India at the end of March I have spent almost every day in consultation with as many of the leaders and representatives of as many communities and interests as possible. I wish to say how grateful I am for all the information and helpful advice that they have given me. Nothing I have seen or heard in the past few weeks has shaken my firm opinion that with a reasonable measure of goodwill between the communities, a unified India would be far the best solution of the problem.

“For more than a hundred years, 400,000,000 of you have lived together, and this country has been administered as a single entity. This has resulted in unified communications, defence, postal services and currency; an absence of tariffs and customs barriers; and the basis for an integrated political economy. My great hope was that communual differences would not destroy this.

“My first course, in all my discussions, was therefore to urge the political leaders to accept unreservedly the Cabinet mission plan of May 16, 1946. In my opinion that plan provides the best arrangement that can be devised to meet the interests of all the communities of India.

“To my great regret it has been impossible to obtain agreement either on the Cabinet Mission plan or on any other plan that would preserve the unity of India. But there can be no question of coercing any large areas in which one community has a majority to live against their will under a government in which another community has a majority — and the only alternative to coercion is partition.

“But when the Muslim League demanded the partition of India, Congress used the same arguments for demanding in that event the partition of certain provinces. To my mind this argument is unassailable. In fact, neither side proved willing to leave a substantial area in which their community have a majority under the government of the other.

“I am, of course, just as much opposed to the partition of provinces as I am to the partition of India herself, and for the same basic reasons. For just as I feel there is an Indian consciousness which should transcend communal differences, so I feel there is a Punjabi and Bengali consciousness, which has evoked a loyalty to their province. And so I felt it was essential that the people of India themselves should decide this question of partition.”

Against this backdrop, Nehru was the man who saw tomorrow. In his mind’s eye, his idea, ideal and idiom of India had been sharply etched as early as his return from England and moulded during his brutal incarceration in the Princely State of Nabha in 1923.

For Nehru, India always meant a whole, not bits and pieces to be handed over by the British on their departure from India. It included the Provinces under direct British Rule and the vast swathes of 565-odd Princely States controlled indirectly by the Paramount Power, where 100 million Indians lived in appalling conditions. Undivided J&K alone was bigger than France; Hyderabad was larger than many European countries.

Nehru’s opposition to the Monarchy — and as a consequence, to the tin pot maharajas who ruled the states by virtue of their treaties and other linkages to the Paramountcy — was almost visceral.

Nehru chose not just to take on the Monarchy and their extension counters in India — the Princes — but he even repeatedly took on his ideological alter ego, Mahatma Gandhi, in ensuring that the Indian National Congress may be allowed to mobilise political opinion in the Princely States as it strived for full responsible governments which reflected a plurality of viewpoints.

For a long time, Gandhi opposed this move due to his own predilection for the concept of ‘trusteeship’, where the princes were to function as trustees and oversee the betterment of the populace under them. His own father, Kaba Gandhi, was Dewan to the Rajkot Thakore. But this concept of trusteeship soon became archaic in a rapidly changing environment where nationalism and freedom became the overriding — and only — objective. Nehru could not understand how the Indians living in the Provinces could be jingoistic, while those residing in the Princely States would remain untouched by the freedom movement sweeping the core psyche of India.This was an anachronism for Nehru; he vowed to fight Gandhi’s policy, which he found to be without a clear direction.

For Nehru, the map of India as it existed was sacrosanct: One free India, without any compromise.

He constantly talked down to the princes and showed them their place. To the main saboteur, Nawab of Bhopal, Nehru wrote: “The destruction of the Princes was bound to happen whether we wanted it or not. All we could do was to see that the changes that were inevitable took place in as reasonable and amicable way as possible.” Within a short span of 21 months, the princes were stampeded by Nehru, Mountbatten, Patel and V.P, Menon using a mixture of threat, coercion, cajoling and grandstanding.

In many ways, the period 1938-1939 was a ‘moment of truth’ in a large number of Indian princely states as powerful people’s movements flourished against the high-handedness of the ruling dispensation which directly drew its strength from the Paramount Power in the princely states.The challenge to the Gandhiji-Nehru-Patel troika also came at around the same time.

At the Haripura Congress, Subhas Chandra Bose became president of the Congress and a year later in Tripuri, he forced the issue again, despite strident opposition from the trio and won the presidency by 95 votes, against Gandhiji’s candidate, Pattabhi Sitaramayya. After Bose’s convincing win, Gandhi said Pattabhi’s defeat was “more mine than his”.

At Tripuri in March 1939, G.B. Pant moved a resolution asking Bose to appoint a Working Committee in line with Gandhi’s ideas. In a passionate presidential address on the princely states on March 10, 1939, Bose’s opinions echoed those of Nehru, as he said, “But since Haripura much has happened. Today we find that the Paramount Power is in league with the state authorities in most places. In such circumstances, should we of the Congress not draw closer to the people of the states? I have no doubt in my own mind as to what our duty is today. … the work of guiding the popular movements in the States for Civil Liberty and Responsible Government should be conducted by the Working Committee on a comprehensive and systematic basis.

“The work so far done has been of a piecemeal nature and there has hardly been any system or plan behind it. But the time has come when the Working Committee should assume this responsibility and discharge it in a comprehensive and systematic way and, if necessary, appoint a special sub-committee for the purpose.” For Nehru, this became a defining moment as it enabled him to expand the scope of the freedom struggle to the princely states.

His early experience in Nabha was not only mind-numbing, but mind-shaping as well. The rulers of two princely states in Punjab, Nabha and Patiala, were locked in a bitter dispute. This resulted in the deposition of Maharaja Ripudaman Singh of Nabha by the British Government of India and the appointment of a British Administrator to rule the state. The deposition of the Maharaja led to a fresh agitation by many Sikhs. Batches of volunteers (jathas) came to Jaito in Nabha state. These jathas were brutally assaulted by the police, arrested, and protesters were later abandoned in remote places in the jungle.

Accompanied by two fellow Congressmen, A.T. Gidwani and K. Santhanam, Jawaharlal Nehru left for Nabha on September 19, 1923. They addressed a public meeting at Muktsar on September 20. The next day, while proceeding towards Jaito, they joined the members of a jatha and were soon halted by the police. The Superintendent of Police asked them to immediately leave Nabha.

They refused, and were immediately arrested under Section 188 of the Cr.P.C. All were handcuffed, and Santhanam’s left wrist was tied to Jawaharlal’s right. A police officer led them through the streets by chain and ordered them to board the evening train from Jaito to the main city, Nabha. The handcuffs were removed only after 20 hours. This spell in jail influenced Nehru to a great extent and he became obsessed with the idea of toppling the princes.

In his book, ‘An Autobiography’, Nehru wrote: “In Nabha Jail, we were all three kept in a most unwholesome and insanitary cell. It was small and damp, with a very low ceiling which we could almost touch. At night we slept on the floor, and I would wake up with a start, full of horror, to find that a rat or a mouse had just passed over my face.”

He wrote of his trial: “… I rejoice that I am being tried for a cause which the Sikhs have made their own. I was in jail when the Guru Ka Bagh struggle was gallantly fought and won by the Sikhs. I marvelled at the courage and sacrifice of the Akalis and wished that I could be given an opportunity of showing my deep admiration of them by some form of service. That opportunity has now been given to me and I earnestly hope that I shall prove worthy of their high tradition and fine courage. Sat Sri Akal.”

It is ironic that the next time Nehru chose to make an example of a Princely State, he again headed for Punjab. This time he raided Faridkot on May 27, 1946. The ruler decided to ban his entry into the state. But Panditji defied the ban and — tearing to pieces the notices served on him under section 144 Cr.P.C. — asked the surging, peaceful mass of humanity to march into the city. The ruler gave way and requested for a compromise.

This was followed by Nehru, president-elect of the Congress, trying to force his way into Kashmir to support his friend, Sheikh Abdullah, who had been imprisoned by Maharaja Hari Singh for sedition. He was stopped in Domel on June 21, 1946, and jailed.

Each time, Nehru made it a point to show that his instinctive hatred for the princes was abundantly clear.

With agency inputs