New Delhi, Oct 27 : The Kashmir story has been nothing but as dramatic as the tale of its accession over these last 75 years. While Pakistan now labels it as an indigenous uprising or they prefer to give it the nomenclature of a “freedom struggle”, the reality is that the seeds of the Kashmir imbroglio were sown in the dark days of the accession.

Under Westphalian sovereignty rules, J&K morally, legally and constitutionally is wedded to India; and Pakistan which sent Afridi raiders to overrun Kashmir in October 1947, has no right over it.

It was around 1931 that the downtrodden populace of the Valley rose to a man against the repressive rule of the Maharaja. They were led by a man who was for all practical purposes a nationalist, though disturbing evidence over time points otherwise.

Sheikh Abdullah, a nationalist who somewhere along the way got boxed in due to the contradictions that traversed the corridors of his mind. In his mind he could never quite define internal autonomy for Kashmir and as such this acquired the hue of independence from the Union of India. His thinking evolved across that vector – from nationalist to preacher and harbinger of autonomy for the Valley. And even tinkered with the idea of an Eastern Switzerland, an independent Kashmir just as his predecessor Maharaja Hari Singh thought of Dogristan an independent entity wedged between the Dominions of India and Pakistan.

Hari Singh’s court’s Rajguru Swami Sant Deo was principally responsible in stoking this notion – to be the sovereign of “an extended kingdom sweeping down to Lahore from the heights of Ladakh”.

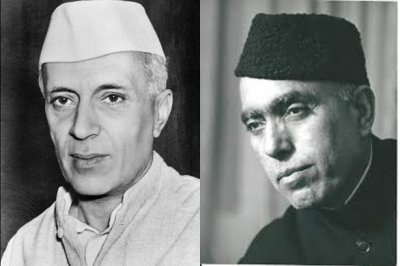

But this story of accession is as much about Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, that titan amongst statesmen, and his friendship with Abdullah. It is also about Nehru’s resolve stoked by his private secretary Dwarka Nath Kachru’s(another Kashmiri) inputs. Nehru was convinced that Kashmir was worth fighting for and he advocated the Mysore Model after its accession. He wanted an interim government in Kashmir based on the Mysore Model. In Mysore, the leader of the popular party was asked to choose his colleagues, he himself being the Prime Minister. His hope sprung from the fact that Sheikh Abdullah, a Muslim leader, and “somebody who could deliver the goods” would lead the state out of the morass that it had sunk into during the Maharaja’s rule.

Economic aspirations and all-inclusive growth were the bulwarks of the New Kashmir movement and this was in many ways Sheikh’s mandate.

This story is also about the princes, of which Maharaja Hari Singh was very much a part of their hopes and ambitions in the run-up to independence and the lapse of paramountcy. Intertwined in this tale is the larger story of the Indian princely order which wanted to turn the flawed two-nation theory into the three-nation theory. They are equally a part of the drama that was unfolding in the days preceding the partition. And finally, the story dovetails the role of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Nehru’s disparate twin as it were in the freedom struggle and formation of India’s first government.

Facilitator of the accession, antithesis of Sheikh, supporter of Hari Singh, acting as a counter weight to the Nehru-Sheikh axis, Sardar Patel stood tall against the princes and their collective and individual intrigues and machinations as they tried to stay out of the ambit of the burgeoning might of the Congress party.

It is also about Mohammed Ali Jinnah, a man who tried his level best till the day he died to grab Kashmir by hook or by crook. A man who visited Kashmir for holidays in the late 1920s and then again in 1936 till he finally arrived for what many describe to a hero’s welcome in May 1944 in both Jammu and Srinagar. This visit in response to an invitation extended by Muslim Conference leaders saw him spending over two months in Kashmir. A semi-official visit where he was deliberately shunned by the ruler and his Prime Minister. And while ostensibly welcomed by Abdullah at Batwara in 1944, who chose to play hide and seek with him. However, in 1936 it was Abdullah who called on Jinnah.

In one of his speeches, Jinnah appealed to the Muslims of Kashmir saying, “If your objective is one, then your voice will also become one, I am a Muslim and all my sympathies are for the Muslim cause.”

It was at Kashif (a house owned by Martab Ali) next to the Nishat that Sheikh met Jinnah. It is believed that after this meeting with Jinnah, Sheikh’s hatred intensified for the man. All told Jinnah stayed for 77 days and spent many days in the house-boat Queen Elizabeth near Lal Mandi on the Jhelum. In one of the rare pictures, Sheikh and Jinnah can be seen in the same frame albeit apart on the AMU bash at Amar Singh club.

Jinnah was also invited by Maharaja Hari Singh in Srinagar where he was warmly received but the Royal Family didn’t engage with him.

In another interaction, Jinnah appealed to the Muslims of Kashmir that “it is better to live in a hut in Pakistan with a sense of security than to live in a bungalow in India under the shadow of security”.

Finally, in his address to the Muslim Conference Session in the compound of the Jama Masjid, he said, “It is my duty as a Muslim to advise you correctly as to which course would be proper and ensure your success.”

Jinnah had come to Kashmir to effectively unify the Muslim Conference which owed its allegiance to the Muslim League and Sheikh Abdullah led National Conference, but this did not fructify. In an emotive speech, Jinnah showed why Kashmir was important to him, “God has given you everything, Kashmir which is known as paradise, the gem in the ring as the world is, and an unparalleled country, what such a country does not possess? Oh Muslims awake and stand up and work hard and bring life to this dead nation.” But Jinnah could never ever convince Abdullah who soon after the former left the Valley attacked him in a series of mass contact meetings, saying that Jinnah should leave the people of the state to their fate, he even threatened to ‘expose him’.

The differences of opinion between Jinnah and Abdullah well and truly cost the former – Kashmir. For the Muslim Conference did not have a leader in Kashmir who could combat Abdullah. And remember, Abdullah had Nehru and Nehru had Abdullah in Kashmir. They together thwarted Jinnah’s subterfuge. Coercive tactics were used by him subsequently to strong-arm the accession, but this did not materialise making J&K the unfinished business of partition for every successive regime in Pakistan.

Let me quote from a confidential note prepared by Dwarka Nath Kachru (PS to Nehru) for Nehru on June 8, 1947, for it offers yet another perspective on Kashmir and its importance to the Indian Union: “Geography, it has been suggested in certain influential quarters, will no doubt play a great part in determining the course which the states would follow. Due to the proposed division of Punjab, it is, therefore, permissible to argue that Kashmir will find itself geographically isolated from the rest of India. Powerful influences may also develop which will tend to draw Kashmir to the new alignment of forces within the areas adjacent to it.”

This story is also about my grandfather, a journalist with Blitz who, like many of that age, was besotted by what Nehru represented. First as chief of bureau of Blitz in Delhi scooping story after story, then as OSD to Nehru, followed by PS to J&K’s first Prime Minister Sheikh Abdullah and then OSD again on Kashmir to Nehru in Delhi for long years, always with a ringside view of historic events in India’s capital and with an astute finger on the pulse on Kashmir affairs, he always had skin in the game. His vast repository of secret and confidential papers, missives, documents, and aide memoirs has helped me re-construct the tumultuous events of the time. The walkabout begins from 17, York Road, the Indian Prime Minister’s residence where the outhouse had my grandfather’s family living in it.

Though Nehru acquiesced to Abdullah’s arrest in Gulmarg in 1953, he never reconciled to it. My grandfather K.N. Bamzai was the centrifugal force in Sheikh’s arrest in the Kashmir Conspiracy case. Late one night in 1953, my grandfather rushed to see Pandit Nehru. He had a letter with him from Bakshi Ghulam Mohd, the deputy Prime Minister of J&K. Bakshi was Abdullah’s right-hand man since even before the accession, but he felt that he could no longer support Sheikh Sahib. Bamzai reached there in the middle of the night, around 1.30 a.m. Nehru was by now living in Teen Murti House. He found the lights on in the first-floor study of Pandit Nehru. Mathai took him to meet Panditji in his study, where he delivered the letter. Panditji looked tired and unhappy.

Soon after this, Abdullah was arrested in Gulmarg and replaced by Bakshi Ghulam Mohd as Prime Minister of J&K. It was not only the Sheikh’s own cabinet ministers who opposed him. He had lost support at the centre too, especially from Maulana Azad and Rafi Ahmed Kidwai. Kidwai was one of those who persuaded Nehru of the need for action and Panditji reluctantly agreed. Nehru was extremely unhappy at the turn of events and he could not reconcile to the incarceration of his friend and political associate Sheikh Mohd Abdullah. Later, when the Kashmir Conspiracy case against Sheikh Mohd Abdullah proved to be weak, Nehru pushed for his release. But Abdullah’s political hibernation lasted till 1975 when the Indira-Sheikh Accord allowed him to return to the centre stage of Kashmir politics.