Redeeming Nostalgia: Divine rhythms and melodies: Naushad’s celestial music and the other ‘secret art’

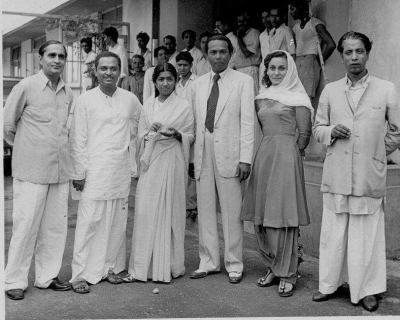

Few music composers can achieve the distinction of their tunes becoming so popular as to be played at weddings — especially their own. Unfortunately, for this particular individual, who reached this pinnacle in his late 20s, it was a time when careers in films were frowned upon and Naushad Ali had to silently listen to both his (oblivious) father and father-in-law roundly abuse those who made it a profession.

And then there is another telling story of how Naushad, who passed away on this day (May 5) in 2006, functioned.

He was recording that matchless melody “Jawaan hai mohabbat” from “Anmol Ghadi” (1946) — the swan song of undivided India — when the director, the redoubtable Mehboob Khan, strode in and began instructing the musicians and technicians on how to go about, and even asked singer Noorjehan to change a note here or there. All Naushad could say was “Everything would be carried out the exact way you want it, Mehboob sahab.”

However, the very next day, Naushad deftly turned the tables. He went to the sets, and was told by the director that they were filming the song he had just recorded. Asking the director’s permission to see it through the camera, he started to ask the staff to move props here or there.

Mehboob Khan’s response was to catch Naushad by the ear and ask: “Hey you ‘laatsahaab’, who do you think you are? Scram, this is not your job. Your job is music direction, direction is my job.” And Naushad quietly said that this was the admission he was waiting for, and to Mehboob Khan’s credit, he realised it — and stuck to it in the next seven films they did together.

That was Naushad for you. His forbearance, and tact, surmounted his innate and vibrant sense of rhythm that saw him enjoy a glittering six-decade-plus career in Bollywood, where he became the only one to compose for both K.L. Saigal and Shah Rukh Khan.

Responsible for the eternal music in many defining Bollywood classics — “Rattan” (1944) — whose tunes were played at his wedding; “Shahjehan” (1946) — the last film of Saigal; “Mela” (1948), “Andaz” (1949), “Aan” (1952), “Baiju Bawra” (1952), “Mother India” (1957), “Kohinoor” (1960), “Mughal-e-Azam” (1960), “Gunga Jumna” (1961), “Sunghursh” (1968), and finally, “Taj Mahal: An Eternal Love Story” (2005), he also stepped in to complete the music for “Pakeezah” (1972), whose composer, his protege Ghulam Mohammad, had died prematurely during the film’s long gestation.

Not only was Naushad’s repertoire marked by seamless weaving in the melodies of Indian classical, the cadences of folk music from all over the subcontinent, and the harmonies of Western classical music, he was also successful in persuading legends such as Ustad Amir Khan, D.V. Paluskar and Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan to sing for films.

And then, he also possessed a secret talent — but that was to be expected, as he hailed from Lucknow, the city of poets!

While he could draw on the services of some outstanding lyricists — Majrooh Sultanpuri, D.N. Madhok,and Khumar Barabankvi — and though his enduring partnership was with Shakeel Badayuni (especially when the singer was Mohammad Rafi), Naushad was himself quite a gifted poet across all forms, from ghazals to nazms and geets, and verses for special occasions as well.

Like his music, which figures in less than 100 films, he went in for quality, not quantity. His collection of poetry, “Athvan Sur”, barely comprises 100 pages of poetry, but what figures is pure gold.

He can’t shake off his actual calling: “Abhi saaz-e-dil mein taraane bahut hain/Abhi zindagi ke bahaane bahut hain” and — in a probable reference to the traditional element in his compositions — “Dar-e-ghair par bheekh maango na fann ki/Jab apne hi ghar mein khazaane bahut hain”.

He also dealt with philosophical thought with a ‘Ganga-Jamuni’ sensibility: “Na mandir mein sanam hote na masjid mein khuda hota/Hami se yeh tamasha hai na ham hote to kya hota.”

He penned a handful of nazms — most of which are related to his profession, such as “Modern Music” (ending with “Sangeet hai ya koi kabadi ki dukaan hai/Saazon ka faqt shor hai sangeet kahan hai/’Naushad’ dua karta hai bas haath uthayen/Sangeet ki kashti ko khuda par lagaye”).

Then, there are his heartfelt tributes: “Naushad mere dil ko yaqeen hai yeh mukammal/Naghmon ki qasm aaj bhi zinda hai voh Saigal”; (Rafi) “Is ki har taan, is ki har lae par/Bajne lagte the khud dilon mein saaz”; (Mukesh) “Jab tak is duniya ki mehfil mein raha tu ae Mukesh/Zindagi ke saaz par tu geet kite ga gaya”, and on fellow composer Madan Mohan: “Apni mauseeqi pe sab ko fakhr hai/Tujh ke mauseeqi ko lekin naaz hai”.

Geniuses are rarely confined to one field.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)