Scientists Find First Clues To Understand Violent Short Duration Flares From A Compact Star of Rare Category

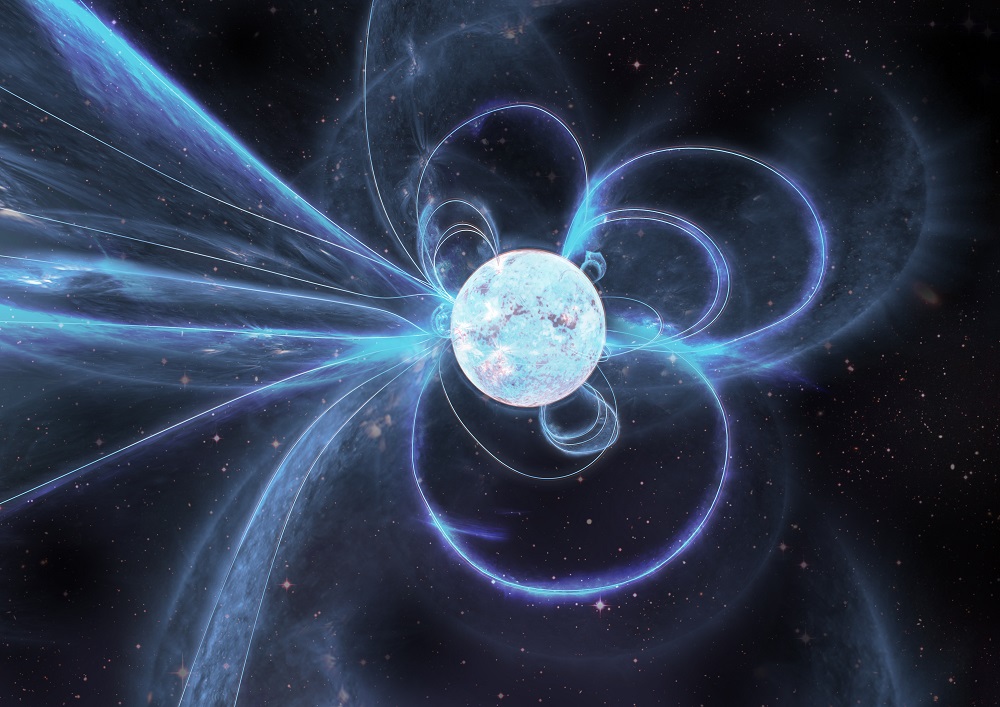

Kolkata, Dec 23 : Scientists have found the first clues to understand violent short duration flares from a compact star of the rare category called magnetar located thirteen million light-years away.

These compact stars with the most intense magnetic field known, of which only thirty have been spotted so far in our galaxy, suffer violent eruptions that are still little known due to their unexpected nature and their short duration.

Scientists have long been intrigued by such short and intense bursts — transient X-ray pulses of energies several times that of the Sun and length ranging from a fraction of a few millisecond to a few microseconds.

When massive stars like supergiant stars with a total mass of between 10 and 25 solar masses collapse they might form neutron stars.

Among neutron stars, stands out a small group with the most intense magnetic field known: magnetars. These objects, of which only thirty are known so far, suffer violent eruptions that are still little known due to their unexpected nature and short duration, of barely tenths of a second.

A scientific group headed by Prof. Alberto J.Castro-Tirado from the Andalusian Institute of Astrophysics (IAA-CSIC) studied an eruption in detail: managing to measure different oscillations, or pulses during the instants of highest energy, which are a crucial component in understanding giant magnetar flares.

Shashi Bhushan Pandey from Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences (ARIES), an Institute of the Department of Science and Technology worked closely with Prof. Alberto Castro Tirado and other group members in this research which has been published in the journal Nature. This is the first extragalactic magnetar studied in details.

“Even in an inactive state, magnetars can be many thousands times more luminous than our Sun. But in the case of the flash, we have studied, GRB2001415, which occurred on April 15, 2020, and lasted only around one-tenth of a second, the energy that was released is equivalent to the energy that our Sun radiates in one hundred thousand (100,000) years. The observations revealed multiple pulses, with a first pulse appearing only about tens of microseconds, much faster than other extreme astrophysical transients,” said Alberto J. Castro-Tirado, IAA-CSIC and lead author.